NO LABLES, NO LIES

Maria Clara Macrì on fashion, photography and belonging

Maria Clara and Mariachiara: two mirroring names, hinting at a connection already written. Almost an echo, recalling the duality that runs through her life and art. As the interview begins on Zoom - one in London, the other in Paris - Maria Clara Macrì’s energy transcends distance, reflecting on identity, photography, and the empathy she seeks to capture in every image.

With a cigarette in one hand and a large mug in the other, she recounts her life as a woman from Reggio Emilia in a family of Neapolitans. “I’ve always lived with this sense of non-belonging. [...] I grew up surrounded by paintings of Vesuvius and parmigiana di melanzane,” she says, laughing. Naples has always been with her, from sweltering summers to long Christmas dinners.

At 18, she moved to Bologna to study Contemporary World History, balancing her passion for art with the stability her parents wished for her. “At university, I painted, wrote, sketched everywhere, and stole my classmates’ cameras,” she recalls, wondering where those first photos ended up. She doesn’t regret her choice: literature, philosophy, and anthropology fueled her thirst for understanding human nature.

After university, a nomadic life took her to London for a couple of years before returning to Naples at 25. “I wanted to get to know it on my own, and that gave me a great push. I rediscovered a part of myself that I had kept hidden.” Belonging and estrangement intertwine in her story. “In Naples, they called me ‘la Bolognese’ because, to them, Reggio Emilia doesn’t exist on the map. But I met so many people.”

“My photography is born from empathy. I connect with people before even capturing them.” This approach guided her latest project, ‘Holy Sciò’: a return to the sacred and profane Naples.

She believes in destiny, and Holy Sciò is proof of that. Years earlier, a chance encounter led her to her now Paris home. “There was this woman - practically me in ten years. After a day spent smoking tobacco barefoot, she told me she had a house in Paris I could moved into when she wasn’t using it, and when she was there, I could stay in her studio in Naples.”

Last summer, that studio gave life to one of her most engaged projects.

Maria Clara’s photography is intimate, built on connection rather than perfection. She sees herself as an explorer of human nature, not just a photographer. “If I hadn’t become a photographer, I would probably have been a psychologist.”

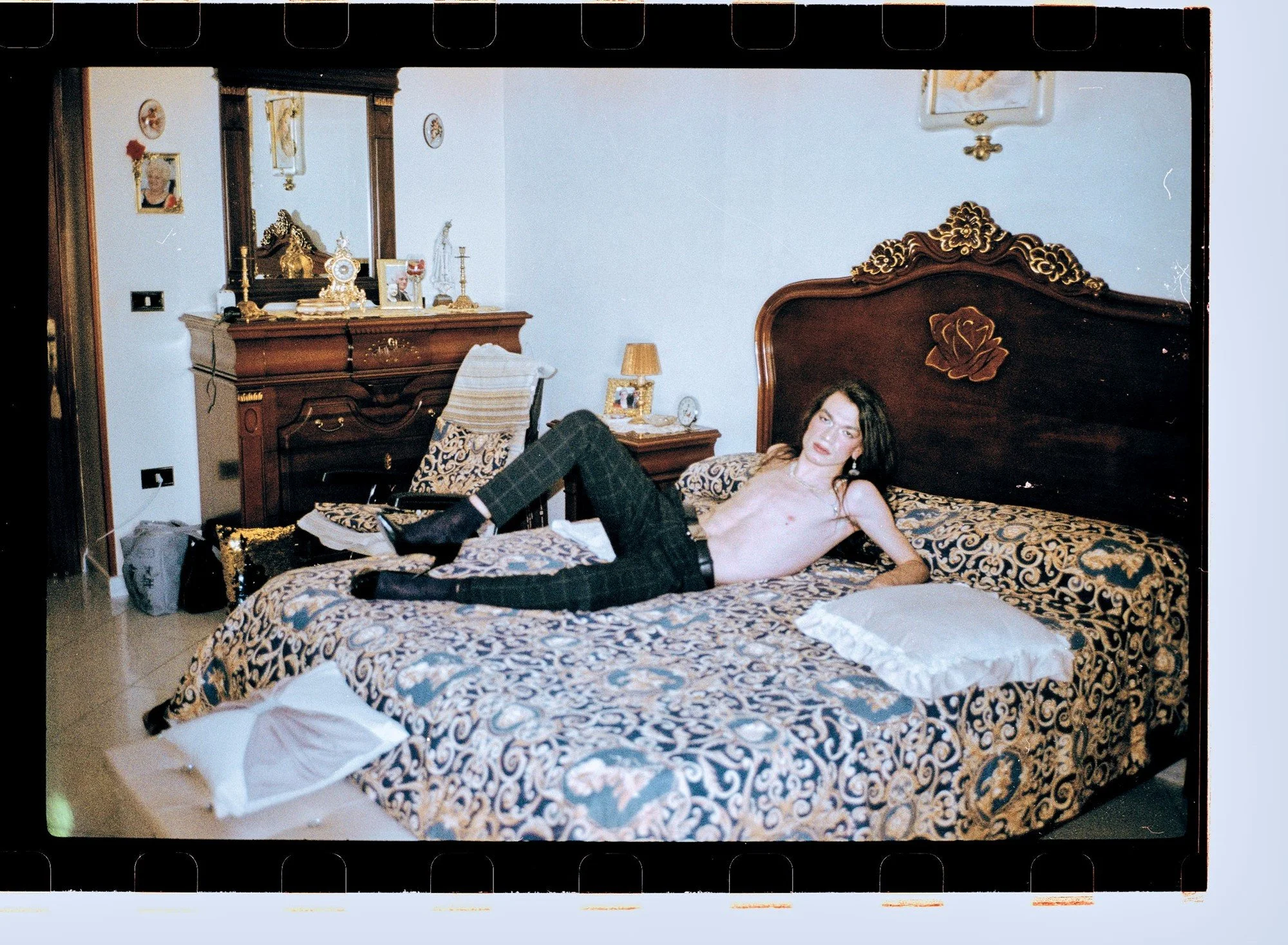

Her process involves hours of interaction before even clicking the shutter. Like with Marco, a young man in transition she met in Naples. “When I saw him, I said, ‘You’re amazing.’ He looked at me, shocked, and replied, ‘No one has ever told me that.’” She spent hours at his home, talking with his mother, grandmother, and twin sister before photographing him. The encounter left her drained but deeply moved.

“His mother told me, ‘I go to therapy only to learn how to make my son understand that I love him.’ I almost cried.” Even my hands tremble as I listen to her. For Maria Clara, photography reveals unspoken truths beyond beauty. Marco is one example, and his mother with him.

After a moment of silence, we resume our conversation with a lighter tone. Despite her success, Maria Clara expresses frustration with photography in the digital era. Social media, she says, has made art a marketplace, sacrificing authenticity to the algorithm. “I don’t even know if it’s the right place for real art anymore.” Instagram’s censorship directly affects her artistic freedom. Her raw, visceral work often challenges norms,but restrictions force her to hide it. “I don’t want to be capitalism’s puppet as a woman, and I don’t want my subjects to be either.”

Unlike many fashion photographers, Maria Clara never followed the traditional route of building a portfolio through agency models and editorials. Instead, brands came to her because of her distinctive, human-centric approach. “To me, fashion is a form of art. A piece of clothing becomes a character, just like a person.” Everything adds deepth to the portrait’s narrative.

She describes her ideal collaboration with a brand as deeply immersive, one where she can soak up the creative vision, inspirations, and philosophy behind a collection.

“I don’t just want to shoot campaigns, I want to enter a brand’s intimacy, absorb it, and build a vision together.”

Her most fulfilling project was a campaign for a new cashmere brand in Reggio Emilia. “What I did with this collection in Reggio Emilia is exactly the kind of work I would love to do with brands.”

But she criticizes the industry for tokenizing diversity. “I hate it when brands include marginalized people just to check a box. You can immediately tell when the soul is missing.” True representation, for her, shows how people live, love, and exist, without fitting into prepackaged narratives. “That’s why, in Holy Sciò, I didn’t exclude any part of Naples. I didn’t stop at stereotypes. I wanted to capture the real city, where identities coexist without labels.”

Maria Clara envisions a future where fashion photography moves past commercial inclusivity to embrace true individuality. Her path is anything but linear, and her art is constantly evolving, shaped by her experiences, the people she meets, and the places she inhabits. Despite challenges, she stays true to her vision. “Often, the people I photograph become my friends. There’s a connection that goes beyond the picture.”

At the end of our conversation, I ask her which brand she would collaborate with without hesitation. “If you had asked me a few years ago, I would’ve said Vivienne Westwood. Now? I don’t know. Who do you see me with?” Among the names mentioned: The Row, Saint Laurent, ALL-IN STUDIO. Later, she sends me a full list of standout brands. Truth is, they’d all benefit from working with her.

Just before we disconnect, Maria Clara bids me farewell with a smile: “Ciao bella, buona vita.” Four words encapsulating the entire conversation: one with a soul in constant evolution, kind, passionate, and profoundly human.

All images courtesy of Maria Clara Macrì